Storyboarding as a research Tool

a Course at University of Zurich Graduate Campus by Tanja Hess

The journey from thesis to premise in storyboarding for scientists allows the depth and complexity of scientific research to be channelled into a form that reaches and appeals to broader audiences. This process requires a deep understanding of both research and the art of storytelling to convey the essence of scientific discovery without losing its integrity.

From Thesis to Premise

Scientific Thesis: In scientific research, the thesis represents the central statement or hypothesis to be substantiated or refuted through research. It is the result of an analytical process and aims to contribute to the knowledge in a specific field of study.

Adaptation as a Premise: In the context of storyboarding for scientists, the original scientific thesis is transformed into a premise suitable for the narrative format of a storyboard. This premise forms the foundation for the narrative and helps to communicate the core message of the research in an accessible and engaging way. The goal is not to reduce the complexity and precision of the scientific thesis but to present it in a form that is understandable to a broader audience.

The Process

Starting Point – Scientific Thesis: The process begins with a clear definition of the scientific thesis or research question. This serves as the starting point for the development of the storyboard.

Translation into a Narrative Premise: The thesis is then converted into a narrative premise that serves as the foundation for the storyboard. This premise summarizes the main message or goal of the research in a way that is suitable for storytelling.

Development of the Storyboard: Based on this premise, the storyboard is developed. This includes the visual representation of the research steps, challenges and discoveries, and conclusions in a narrative form that reflects the original thesis.

Communication with the Audience: Finally, the storyboard serves to convey the research and its significance to a wider or non-specialist audience. The narrative form allows for complex scientific concepts and results to be presented in an understandable and engaging way.

The transition from thesis to premise in storyboarding for scientists allows for the depth and complexity of scientific research to be presented in a form that reaches and appeals to broader audience layers. This process requires a deep understanding of both the research and the art of storytelling to convey the essence of scientific discoveries without losing their integrity.

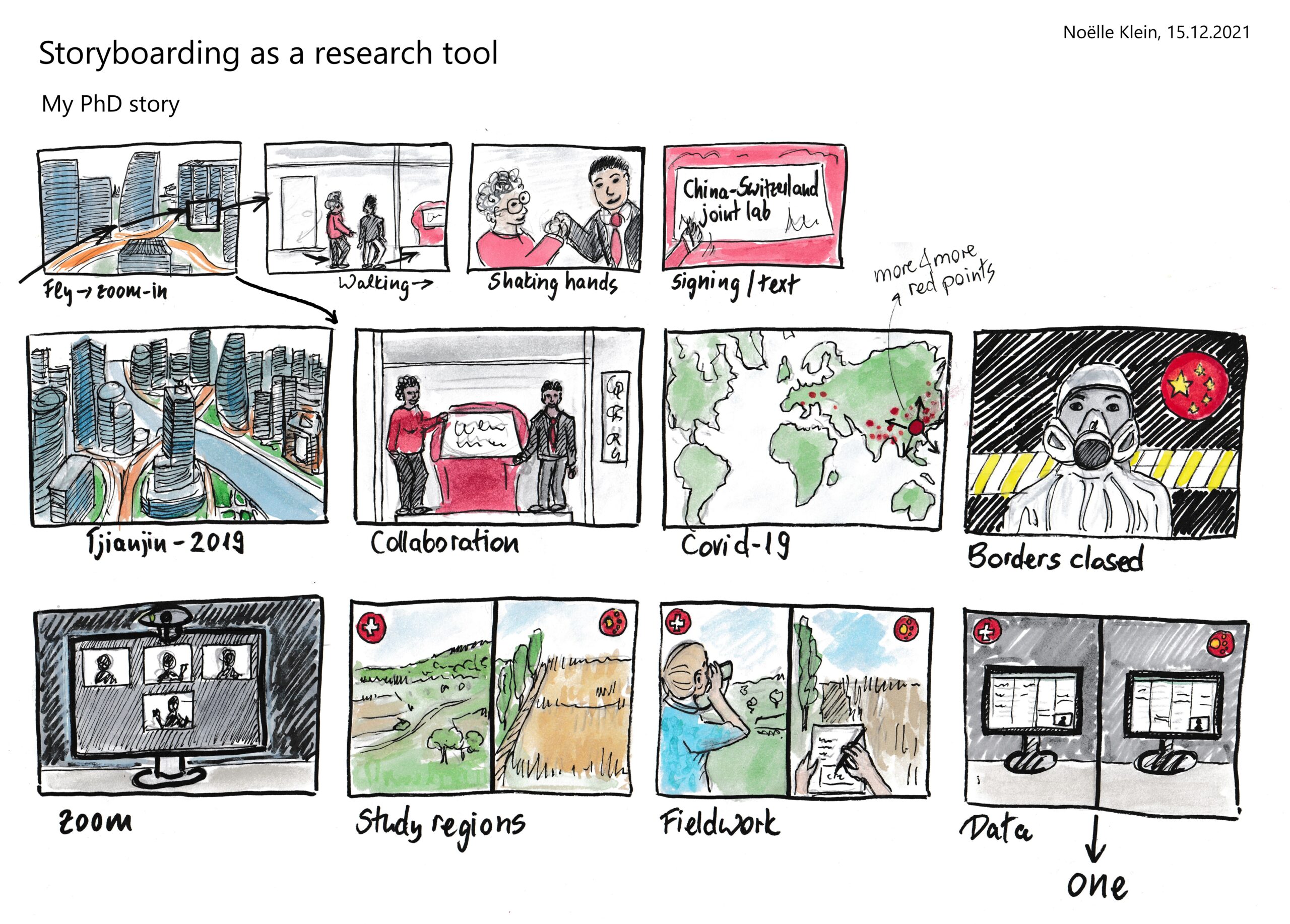

A very good example

Script to the storyboard

The plot premise is: A researcher discovers a serum that makes people immortal.

A worldbuilding is something like: Imagine a world in which immortality is possible thanks to a serum.

Why are Hand-drawn Sketches Beneficial?

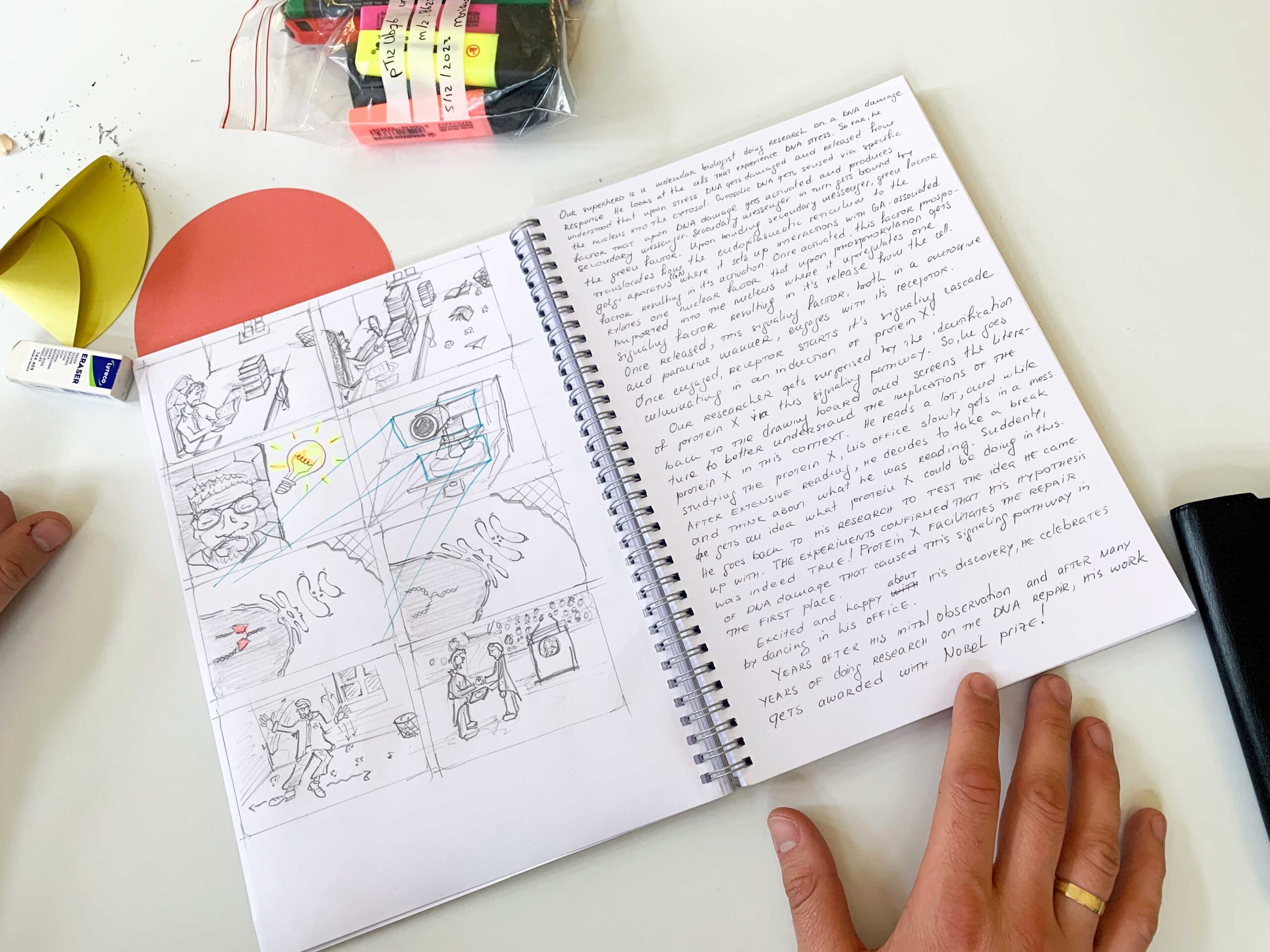

Hand-drawn sketching allows for quick jotting down of ideas without getting bogged down in technical details. It offers the flexibility to spontaneously change or expand concepts, especially valuable in the early stages of idea generation.

Personal Touch

Hand-drawn sketches bear the creator’s personal touch, adding a unique quality to the presentation. This individual touch can highlight the story behind the research and emphasize the human side of science.

Accessibility

Not every doctoral candidate has advanced digital drawing skills or access to specialized software. Hand-drawn sketching requires only paper and pen, making it an accessible method for visually representing ideas.

Storyboarding, complemented by the power of hand-drawn sketching, is a potent tool for doctoral candidates to communicate their research in a manner that is both profound and extensive. By learning to translate their scientific discoveries into storyboards, they can effectively present their work not just within the academic community but beyond. In a world where science and research play a pivotal role, the ability to communicate complex ideas understandably and appealingly is invaluable. Storyboarding for scientists opens up new avenues for sharing knowledge and fostering understanding across diverse audiences.

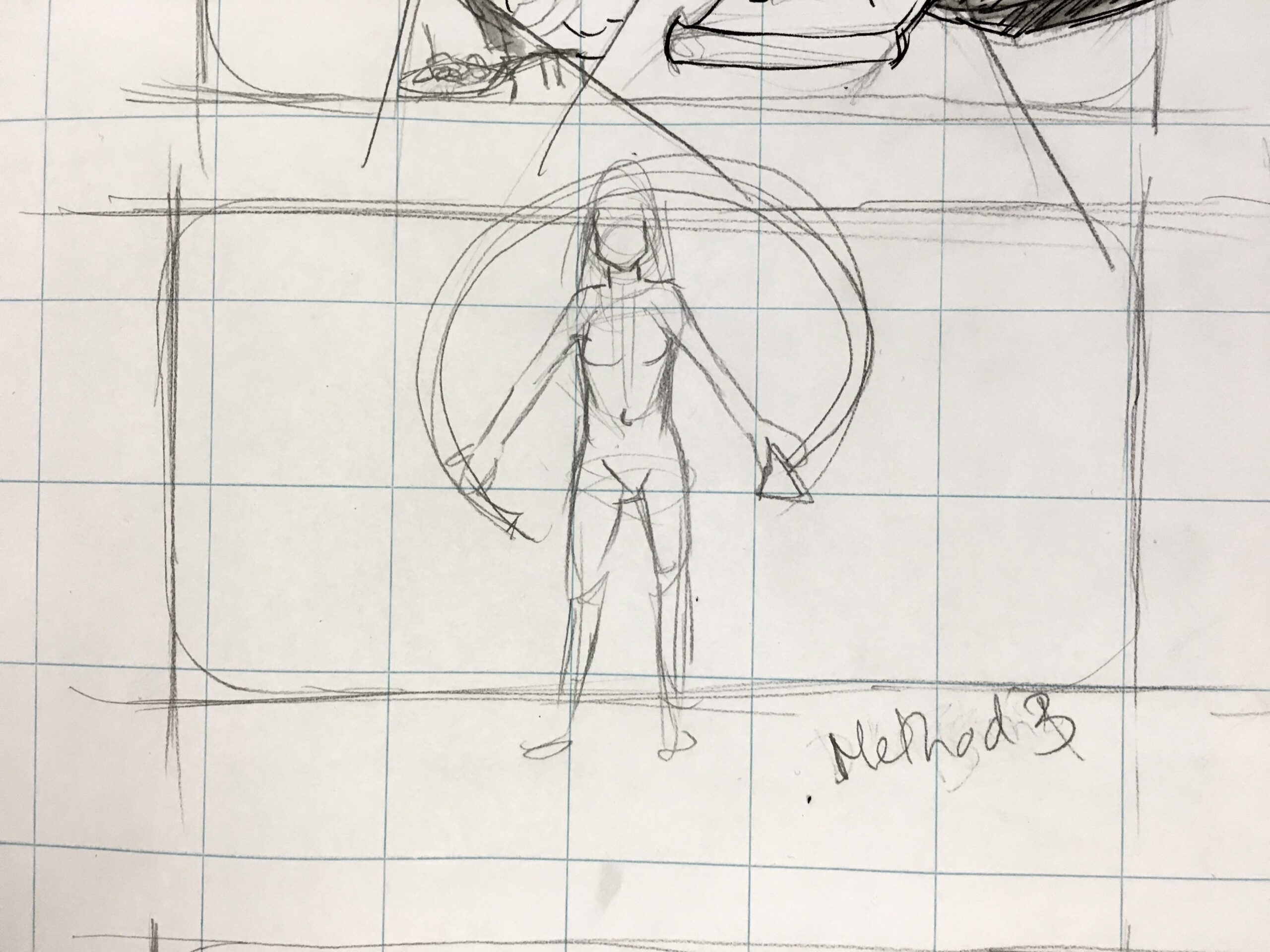

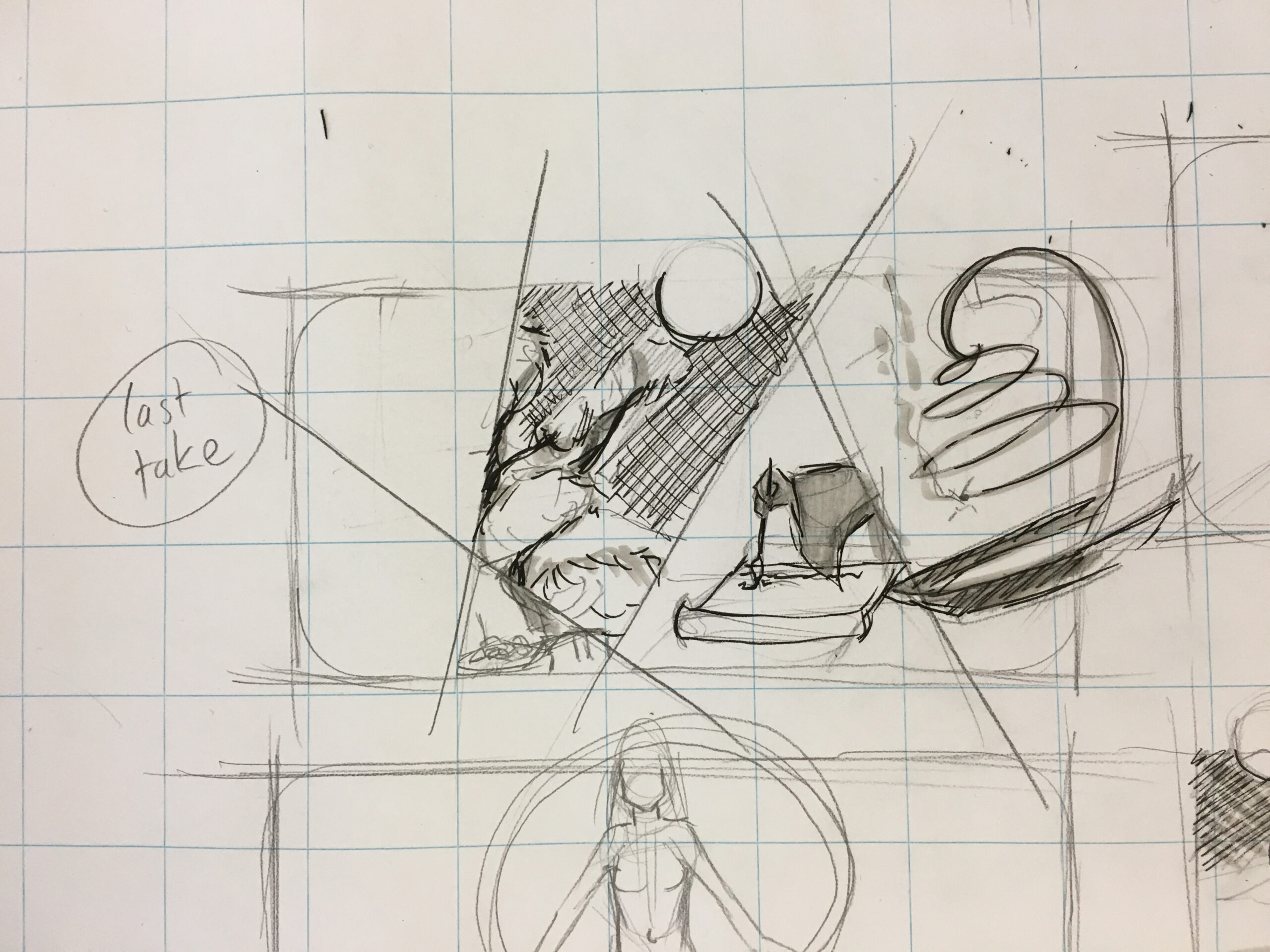

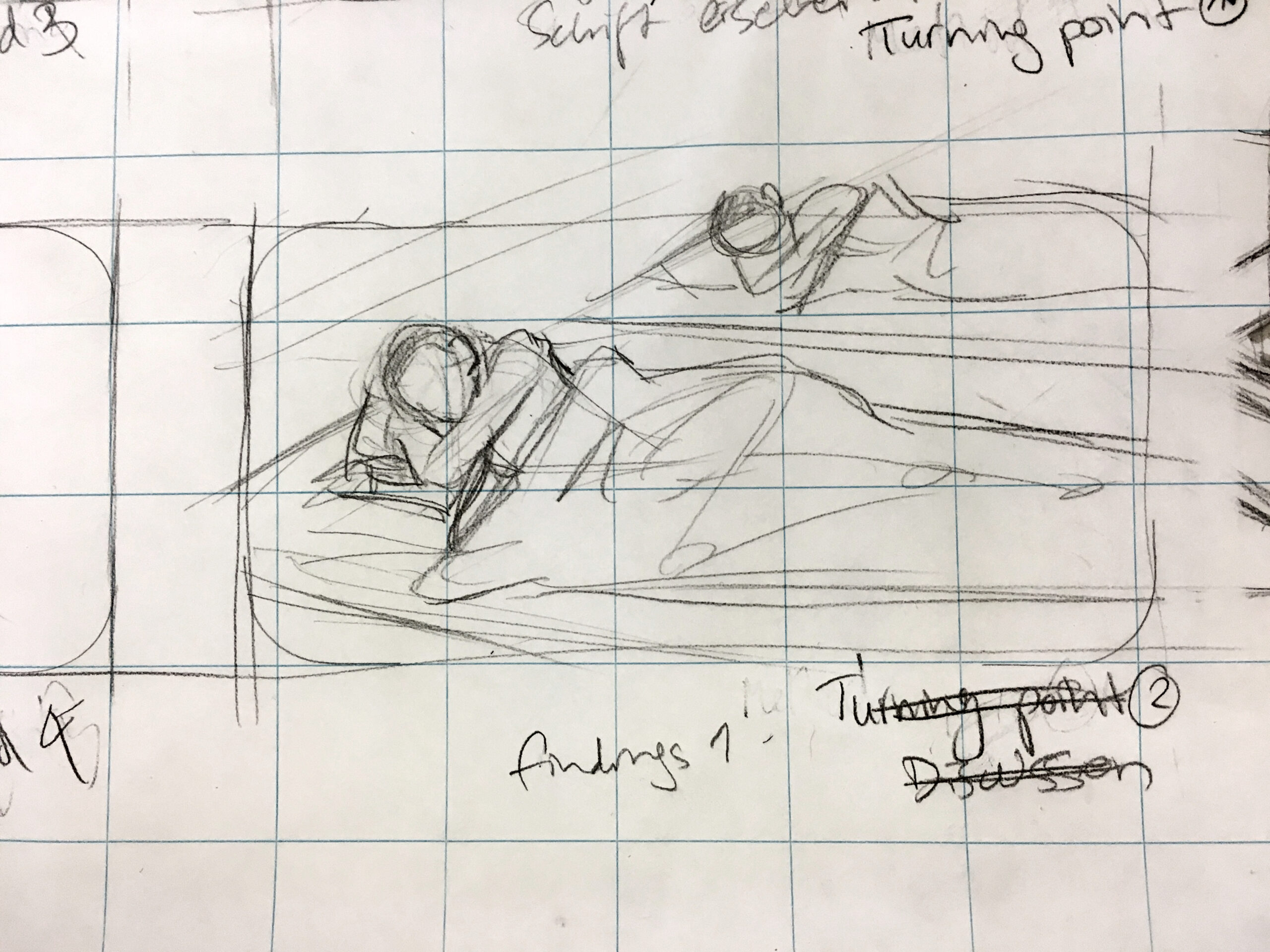

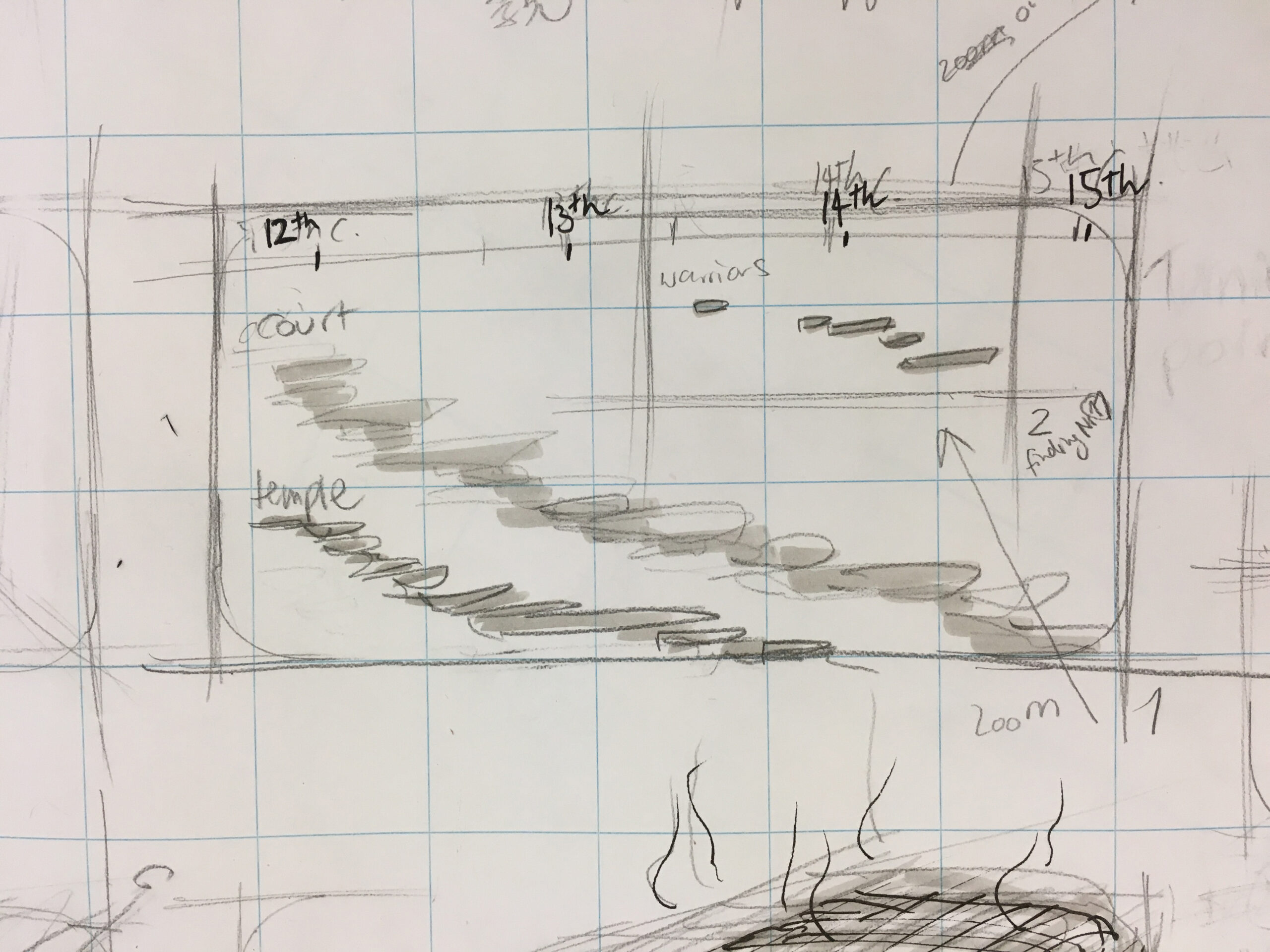

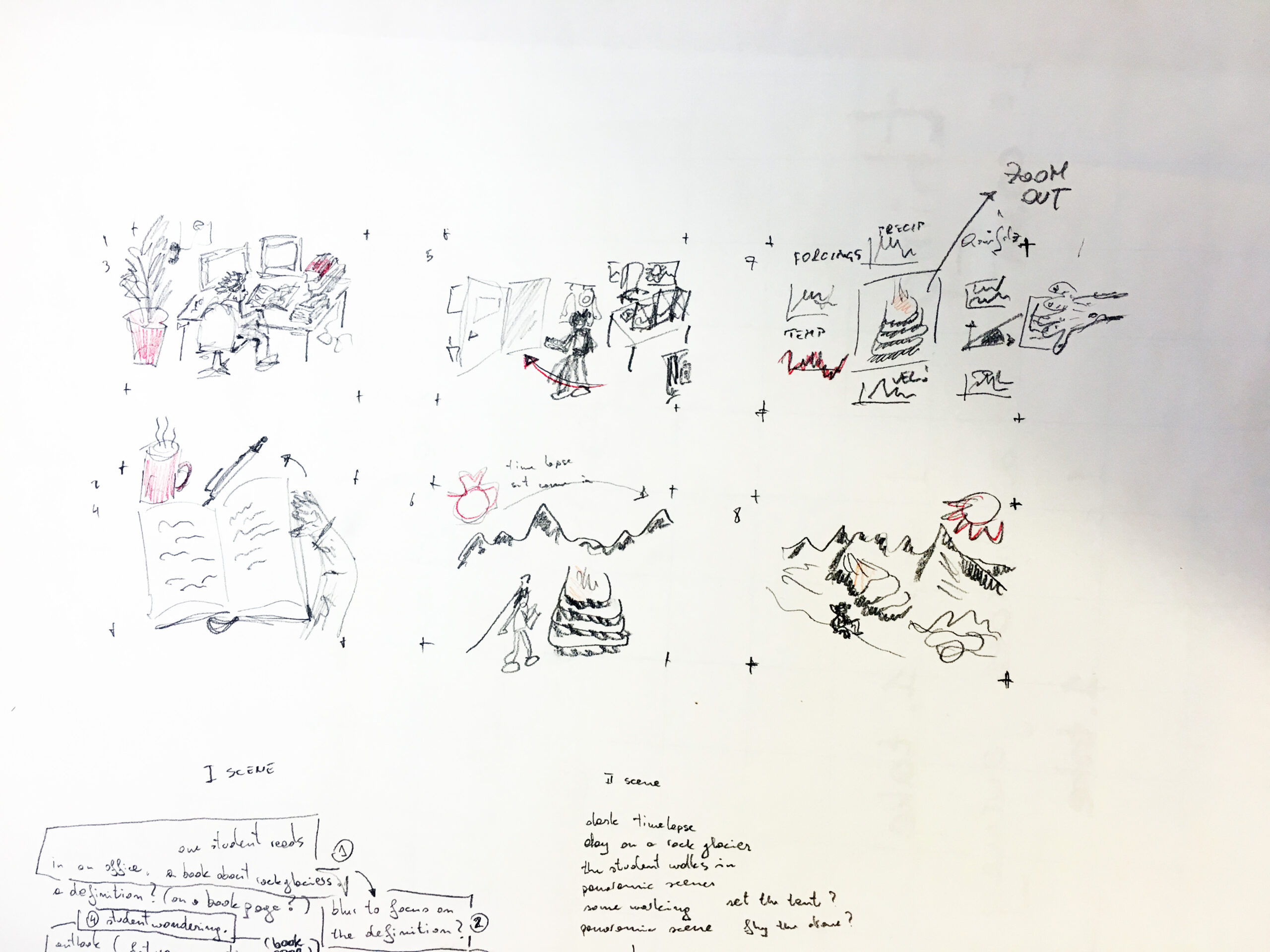

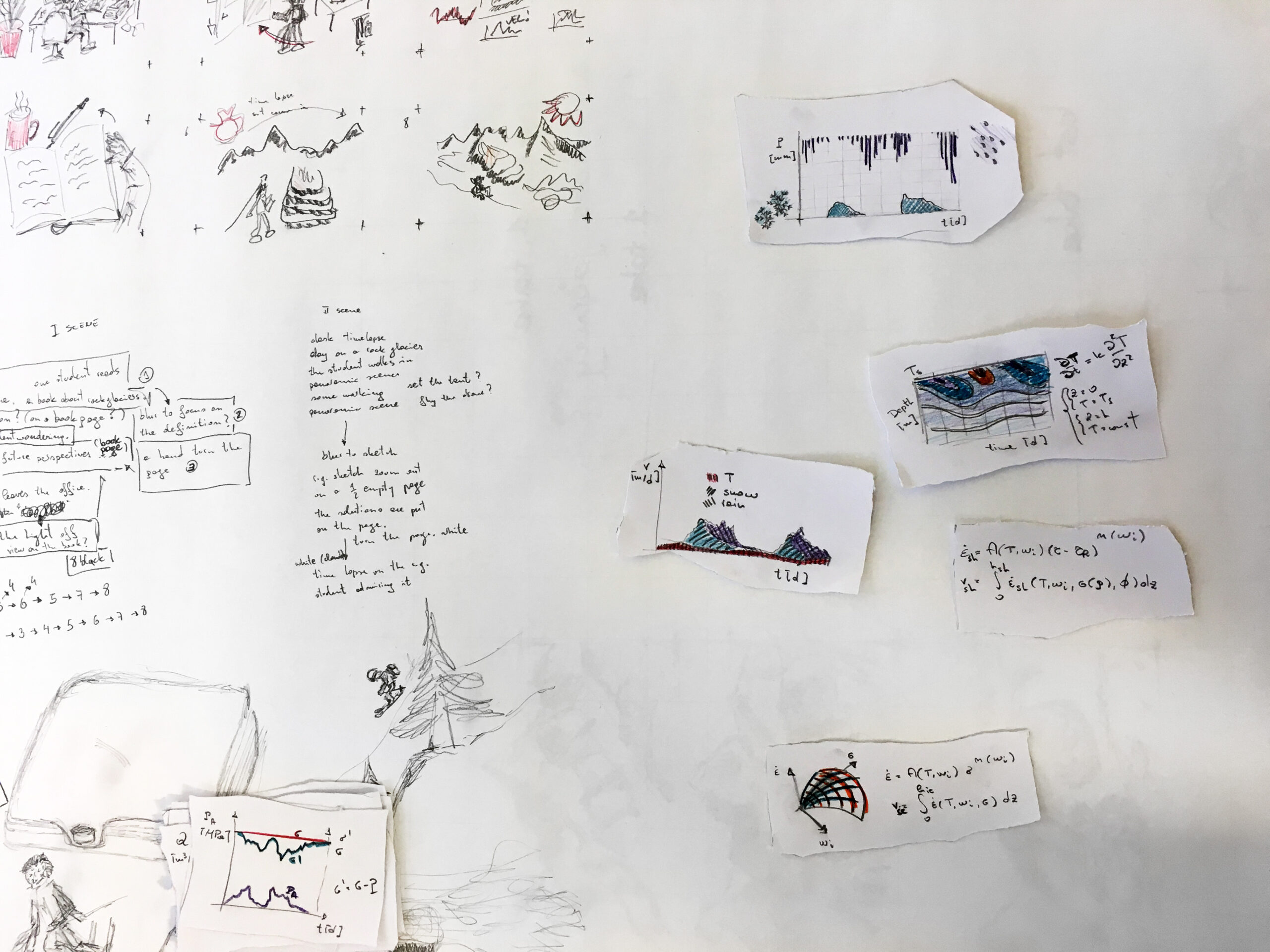

Some impressions from students sketches

An Essential Tool for Doctoral Candidates

In the realm of science, it’s not just about data and discoveries; it’s also about effectively communicating those insights. For doctoral candidates standing at the threshold of their scientific careers, the ability to convey complex ideas clearly and engagingly is crucial. This is where storyboarding comes into play – a technique traditionally used in the film and animation industry but equally valuable for depicting scientific research. Utilizing sketching in the storyboarding process allows doctoral candidates to transform their research into a narrative form that is both informative and captivating.

Why is Storyboarding Important for Doctoral Candidates?

Creating an effective storyboard requires researchers to structure their thoughts and carefully consider which information is most important. This process fosters clear thinking and helps identify the core message of their research.

Encourages Creativity

The physical process of drawing can stimulate creative thinking and lead to unexpected connections or ideas. Hand-drawn sketching provides a freer, more intuitive approach to information representation, inspiring innovative solutions and presentations.

Improves Communication Skills: Storyboarding forces doctoral candidates to think about the best way to present their research to a broader audience. It encourages them to translate complex ideas into understandable concepts, a skill indispensable in science communication.

Facilitates Interdisciplinary Collaboration

In today’s interconnected research world, the ability to communicate across disciplinary boundaries is more important than ever. Storyboards can serve as a universal language, enabling scientists from different fields to share ideas effectively and collaborate.

Increases Engagement and Attention

A well-crafted storyboard can capture the audience’s attention and foster a deeper understanding of the presented research. The narrative structure and visual elements engage viewers emotionally, helping them retain information better.

Handouts to download for PhD Students Zurich University, Graduate Campus

Here you can see how the storyboard and film takes correspond.

The intro to Apocalypse Now begins with a still jungle, accompanied by the haunting strains of The Doors’ „The End.“ Suddenly, the quiet is shattered as napalm engulfs the trees, flames consuming the landscape in slow motion. The sound of helicopter blades merges with the music, creating an eerie, dreamlike rhythm.

Captain Willard’s face appears, upside down, superimposed over the burning jungle. His hollow stare reflects the toll of war as a ceiling fan above mimics the helicopter sounds. Smoke, fire, and destruction dissolve into one another, setting the tone for a journey into chaos and madness.

only for enrolled students

Zwischen Film und Kunst

Storyboards von Hitchcock bis Spielberg, Kunsthalle Emden, 2011

Some pictures from the course

There are two different story plots

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, proposed by Ursula K. Le Guin, posits that the first tool was a container rather than a weapon.

This theory challenges the traditional, conflict-driven narrative frameworks by suggesting that stories, like early human survival, are more about collaboration, gathering, and carrying things together—about holding rather than piercing.

Le Guin argues for a shift in storytelling from the hero’s conquest and linear narratives to those that emphasize collectivity, relationships, and the significance of the seemingly mundane.

From hero’s conquest to carrier bag

It’s a call to value stories that bring together, that nurture, and that focus on the journey rather than the destination.

This theory not only invites a reevaluation of what stories we tell but also how we tell them, championing narratives that encompass the full spectrum of human experience.

1. What is the central problem or question of your research?

This question helps students to identify the core of their research and understand why their work is important.

2. What motivated you personally to work on this research topic?

Personal stories and motivations can make research work more tangible and interesting to outsiders.

3. What challenges did you face during your research?

Conflicts and challenges are key elements of any good story. Sharing difficulties can emphasise the humanity and struggle behind the scientific quest.

4. Was there a turning point or a surprising discovery in your research?

Turning points add tension to the narrative and keep the audience interested.

5. How did you overcome these challenges or what did you learn from them?

Answers to this question show growth and development, important aspects of any story.

6. How does your research impact your field or society?

This question helps students consider and communicate the significance of their work in a larger context.

7. Can you describe a person (real or hypothetical) who is or could be directly affected by your research?

Introducing a human element makes the story more accessible and emotionally resonant.

8. What would the world look like if the problem your research addresses was solved?

This future-oriented question encourages you to think about the long-term goals and dreams of your research.

9. What metaphors or analogies can help explain your research to a lay audience?

Metaphors and analogies are powerful tools for making complex scientific concepts accessible.

10. What is the most important message you want to convey with your research?

This final question helps students to focus their thoughts and define the core of their „story“.

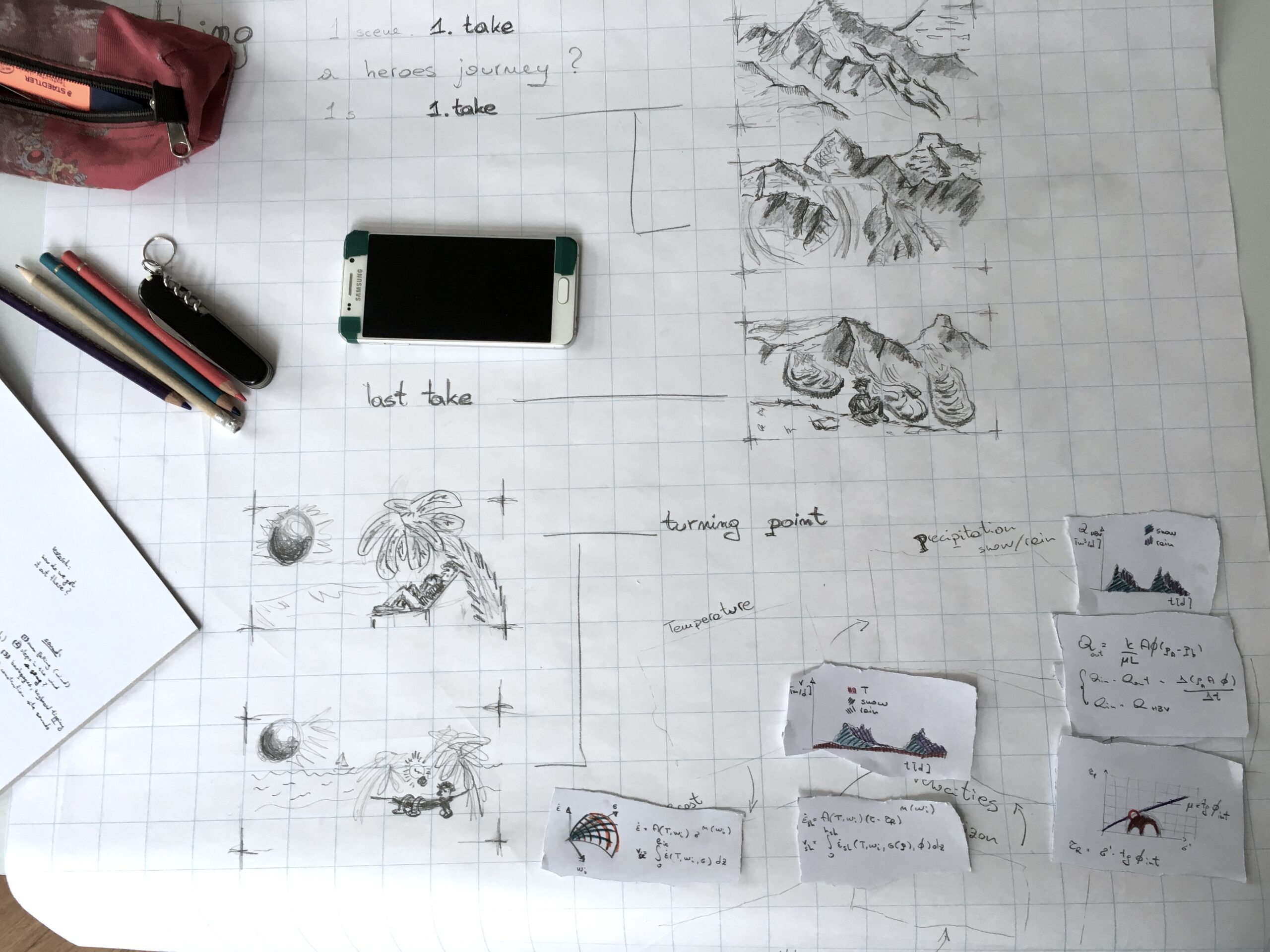

You start your story with the establishing shot, then the closeing shot.

Then you are sketching the finding situation.

After this you head over to the gain or take home … then the first and second obstacles.

So you are going to narrow down the story with always further sketches that are the in bethweens … till you have all the sketches for all the needed takes.

Impression from a workingdesk